- Home

- Mary Horlock

The Book of Lies Page 3

The Book of Lies Read online

Page 3

You see, when Dad was alive, our ye olde family business, The Patois10 Press, wasn’t much of a business at all. Dad’s books never sold as brilliantly as we’d hoped, and we were always tripping over them. Even his magazine, The Occupation Today, which had real-life subscribers and contributors, was running at a loss. Without Mum’s common sense we’d have definitely gone bankrupt. Dad couldn’t accept the trouble we were in because he didn’t care about money/my schooling. Mum said that he was so wrapped up in the past that he couldn’t think about the future. She said you can’t change History – the things that have already happened – but the future is wide open.

Now, Mum reckons what’s ahead makes her happy and I should want her to be happy. Isn’t that what all children want for their parents?

And yes, I do admire her, because she kept up appearances and pretended things were fine, when they really weren’t. It was a bit like when the Germans invaded Guernsey: most islanders tried to ignore them and carry on like normal. This is called sang froid, which sounds better in French, because in English it’s cold blood. I wouldn’t call Mum cold-blooded, but she is a pragmatist, and it’s a shame Dad won’t see how she’s transformed the business. A third of Guernsey’s advertising flyers are now produced by The Patois Press, and we’ve (trumpets, please) just launched our first-ever Escape to Guernsey Calendar.

Mum, it turns out, is an excellent businesswoman.

Which is why she wasn’t around much after Dad died, and why she never noticed when Nic started to come over. I’m not blaming her (really, I’m not), but because she was always working Nic and I could please ourselves. Nic really liked our house – I thought it was shabby compared to Les Paradis but she called it ‘real’. She snooped in every room and Dad-filled cupboard and decided that this room, Dad’s study, was the best place to sit. It was seven months and eleven days since he’d died and not much had changed. I thought she’d find it creepy but I remember her sinking onto some cushions on the floor and looking right at-home. After that the study became our den, and nobody noticed the mess we made because it was a mess already.

At first Nic made me nervous. She was the expert in sex and boys and make-up, none of which I knew about. I usually hate it when someone knows more than me, but Nic had this way of talking. She was so honest and I felt like we could tell each other (almost) everything. She actually listened to me, as well. She couldn’t believe it when I told her Mum and Dad had slept in different rooms, and that we weren’t allowed a TV, and that Dad’s fingers had turned black and died before he did. I remember feeling so proud when she lifted up her head, scanned the dusty shelves and said: ‘. . . and I thought my parents were fucked.’

I was the only girl in our class with a dead dad and it made me demi-exotic. Nic wasn’t scared of death, like some people. Is that why she liked me? I don’t know. I just don’t know! She definitely liked Dad’s study, though, and in between plucking off my eyebrows/trying to pierce my ears I told her grisly stories about the German Occupation.11 They were much better than the brainless trash you read in Jackie or Just Seventeen.

But the one story I couldn’t tell her was the one she most wanted to know. I had this huge pile of papers that I’d been carefully putting in order. I’d labelled it ‘The Whole Grim Truth’ (very catchy, I know), because it was the story of Uncle Charlie, Dad’s older brother, who got in trouble with the Germans and ended up being starved and tortured and driven mad. He only just survived the War and he was the reason Dad made himself an expert on said German Occupation.

Nic wanted to know what Charlie had done to get in so much trouble, but I decided not to tell her. I just said he chose the wrong friends, which I think was good and tactful.

Of course she was disappointed and wrinkled up her pretty nose.

‘What? That’s it?’

‘Trust me,’ I replied, ‘that’s enough.’

Then we stared at each other for ages, until she blinked and I won.

‘You should have a drink.’ I pointed to the desk. ‘Third drawer down on the left.’

She reached over and pulled at the drawer and a half-drunk bottle rolled towards her.

Whisky, of course. That was definitely one of my top-ten moments.

I’d never have dared drink Dad’s whisky before, but now it felt better than perfect. Very soon Nic started doing impressions of people at school. She was very good and would’ve made a brilliant actress or model or TV presenter. After she’d done Mrs Queripel with her manic-secret-nose-picking, she did Adèle Mauger and her dying-pig laugh, then she jumped up and grabbed a wad of papers.

‘Well! Top marks again, Cathy, you bring History to life! Gosh, you put us all to shame. I’m rather overcome. I can’t hold back any longer. Come here and give me a kiss.’

She leaned in and puckered up and I had to burst out laughing. It was a pretty good impression of Mr McCracken, our form teacher, who also taught History, which was (of course) my best subject.

‘He thinks the sun shines out of your arse, and he’s your next-door neighbour. Star-crossed lovers!’

I pointed out that Mr McCracken lived three doors down at La Petite Maison, and that star-crossed meant doomed.

‘Still. He’s obviously into you, the way he always smiles at you and talks to you after class. I mean, what a sleaze. He’s gagging for it.’

I shrugged.

‘And do you see him much out of school?’

‘On the cliffs sometimes.’

Nic fluttered her eyelashes and crossed her hands over her heart, ‘I bet he plans it! So it’s like you and him and the wind and the waves?’

‘No.’

‘Well, it should be! What are we doing here? Let’s go and find him.’

I’m glad to say we didn’t find him that day. If we had, I’m sure Nic would’ve embarrassed me horribly. She could make me blush tomato-red, and teasing me about Mr Mac became her favourite sport. So what if I played along. That’s not a crime, is it? And I didn’t take it seriously – it was just a silly game. If she was rude about him it annoyed me, but what could I do? I knew that our friendship wasn’t equal. I suppose it was more like a marriage, where one person is always more in control. Nic was beautiful, so she could do and say whatever she wanted. I didn’t think of myself as weak or under her thumb, I just thought I was happy. I’d always said and done everything right up until then but I hadn’t felt alive.

Most people are not by nature good – they’re just afraid of getting caught being bad. Even Mr McCracken. Poor Mr McCracken. Mrs Perrot had told him to be firmer with his pupils, but he wasn’t really built for it. He’d always say ‘Please’ and ‘Now, quiet. . . that’s enough!’ and blush as badly as me. Maybe it didn’t help that he had cheekbones like cliff edges and all that flicky hair. But what was he thinking, coming to work at an all-girls’ school? Talk about asking for trouble.

Nic was trouble. She said I was his pet but it was never like that. I was polite and attentive to all of my teachers. Maybe I was more relaxed around Mr Mac, but that was because I saw him all the time – in his garden and cleaning his car, and out on the cliffs with his camera. He was a mad-keen photographer and used to wander on the beach for hours, fiddling with his lenses.

Just to be clear, when I went out on the cliffs I didn’t go because Nic suggested it, and I wasn’t in search of Mr Mac. No. Not at all. I just went to check the Moorings, like I did every week.

The Moorings are these slime-covered cement steps that wind down the side of Fermain Bay. If the tide is high enough you can dive off them into the sea, but at low tide you can walk straight onto the beach. Dad used to time his swims precisely so he could dive off them every day. Have I mentioned he was a champion swimmer? He wasn’t bothered by the sub-zero temperatures.12 He could execute a perfect dive off the top landing and he sometimes didn’t surface for a full five minutes, and by then he was already halfway across the Bay. He’d power through the water like a propeller on a speed boat.

Dad was so fit

and healthy, much fitter than Mr McCracken. Mr McCracken definitely couldn’t dive. He’d snap in two! That’s probably why he was embarrassed when he found me clearing the stones on the beach. It was a wet and windy Sunday (a lot like today) and I was on my knees in soggy sand. I tried to explain how divers might cut themselves on any sharp rocks and that Dad had always done it, just to be sure. But Mr Mac looked at me like I was a nudist.

‘Well, maybe I’ll find something else, like an unexploded land mine or an ammunition dump.’

Mr Mac inspected the sky (which was all sorts of grey).

‘Now that would be something.’

I nodded back and relaxed my grip on a smallish boulder. I wanted to ask after his wife, because I hadn’t seen her in ages. Mrs McCracken was an artist before she packed her bags and demanded a divorce. I think she designed school badges or something quite particular. She had thick, wiry hair and always wore skirts that skimmed around her ankles. Dad had called her a hippy, which was a bad thing.

I stared out at the empty sea and wondered what to say, but before too long Mr McCracken pepped up.

‘Your father swam whatever the weather. I’d see him down here even on the wildest of days. I used to think he had webbed feet!’

When I was little Dad had let me perch on his feet while he did his sit-ups and I recall he did have very long toes. But he’d stopped doing those exercises a long time ago. He’d also stopped swimming although no one had noticed. I’d see him set off for the cliffs with his trunks rolled up in a towel and I should’ve wondered why, when he came back, his hair was still bone-dry.

Mr McCracken asked after Mum and called her a Trooper, but I thought he said a Grouper, which is a fish. I replied that Mum didn’t like water and hot climates. We stared at the steps and the seaweed and the rocks.

McCrackers looked slightly dazed.

‘I love the sea here. I’ve been all over the world but there’s no sea like here.’

He had been to Australia and swum with dolphins and climbed Ayers Rock. He had also scaled the pyramids of Egypt.

I asked if it was true that all the people who had built the pyramids had been buried alive in them.

‘No, that’s a myth. But when the pharaoh died his family would kill themselves so that they could join him in the afterlife. All his belongings were buried with him, all his treasure, as well.’

I then told Mr Mac how the Germans had buried slave workers in the bunkers and tunnels by accident on purpose.13 McCrackers said a lot of the stories about the German Occupation were exaggerated, so I offered to drop round spare copies of Dad’s many books and pamphlets.

I don’t want to bang on about it, but Dad really was Guernsey’s Most Famous or Notorious Modern Historian. He knew everything about the German Occupation. He was even an expert on the bunkers and fortifications, and there are a lot of them, too, because when the Germans came they were worried the British would want us back.14 The Germans are not known for their architecture (I have seen pictures of Frankfurt) so you can imagine what carbuncles they created. Dad called them OUR CROWNING HORROR but was always campaigning for their upkeep.

Mr Mac began to look Mc-worried.

‘You must be lonely without your father.’

I stroked my imaginary philosopher’s beard. ‘But I was lonely when he was here. He was so strict: he never let me do anything. I mean, at least now he’s gone I can go out and have some fun.’

Mr McCracken nodded gravely (no pun intended), then he said I was brave for putting on a face. ‘Your classmates won’t understand what you’ve been through. Children – teenagers especially – can be cruel, and they’ve got short memories. I hope they don’t expect you to bounce back and be normal.’

I reminded Mr Mac that I was never normal, and he laughed.

‘Yes, Cathy, but even so.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I replied, staring out to sea, ‘I know only too well how children can do and say terrible things without realising the consequences. They can cause terrible harm and possibly also death. Nobody understands death until it happens to them.’

Mr McCracker’s eyes twitched and he asked me what I meant. So I explained how Dad’s elder brother was my age when he betrayed his entire family to the Nazis, shot his father in the head and was then sent to a concentration camp.

I was aware, as I was saying it, that I’d got the facts slightly muddled, but I didn’t like to backtrack. Mr Mac looked both puzzled and nervous, which seemed like a good combination, and I just wanted to leave it at that.

13th December 1965

Tape: 1 (B side) ‘The testimony of C.A. Rozier’

[Transcribed by E.P. Rozier]

(Check patois with Mrs Mahy)

Emile, I killed your father. He was my father, too, but I never did deserve him. J’ai bian d’ la misère! I’m sorry for what you have lost and how you have suffered as a consequence of my actions. A son needs a father to guide him, and you never knew yours. What damage I did! I was meant to help him with the business and that was the promise I had made. With the schools closed I swore I’d not be idle. I said I’d work alongside him, make him proud.

I may as well have shot him in the head, then and there.

Mon poure Hubert, how little we understood each other. Few would know by looking at this stick of a man that he’d been gassed and imprisoned by the Boche once already. The only clue was in the hacking cough, that terrible weakness in his lungs. Tch! It is a curse on me, that I saw him as a weakling whereas once he’d been a hero. A braver man and a better soldier than I could ever be.

I’d never imagined those delicate fingers pulling a trigger and killing someone, and I didn’t even know he’d owned a gun until he’d given it up. Earlier that month we’d been ordered to surrender all our weapons to the local authorities. They’d collected our rifles, machine guns, shotguns and air guns and dumped them in the sea. Make sense of that! We were to be left completely defenceless. At least La Duchesse had her wits about her. She took our meagre savings out the bank and hid it in Pop’s strongbox under a floorboard of the spare room.

‘Forget it is there,’ she told me. ‘Nobody will lay their hands on what we have worked so hard for.’

Au yous, we were burying our secrets underground long before the Germans even came, and others still were burying their heads. Our lily-livered constabulary were saying ‘The Germans won’t bother with us. We’ve got nothing to offer: a small town, a few shops . . . what use are we to them?’ The only person who kept busy was Ray Le Poidevoin. He had set himself up as a petty dictator with a makeshift army underneath. Not a bad outfit, truth be told. Together they were taking full advantage of everyone’s indecision, clearing out shops and abandoned houses, claiming livestock and God knows what. I heard they’d had a good few parties on those nights before the Hun took hold. To me that didn’t look too brave or soldier-like, to go stealing other people’s stuff. Ray said it wasn’t stealing, though, since shopkeepers wanted rid of their stock before the Hun came.

You should’ve seen the scuffle outside Ogier’s, our one decent shoe shop, after some old stock had been left out on the pavement. There was Ray right in the middle of it, trying to match some ladies’ boots. When I found him squatting there I couldn’t help but smile.

‘Don’t think they’ll fit you,’ I said. ‘And they’d make a funny kind of weapon.’

Ray was a big lad and could’ve cracked me like an egg so I don’t know why I had to taunt him.

‘You make a lot of noise for a little man.’ He straightened up. ‘Seeing as you know so much: how long will the War last?’

I told him nobody knew that.

‘Right, then.’ He pointed to my feet. ‘And how much longer will the soles on those shoes last?’

I stared down at my battered sandals. Le fishu Ray, he had a point.

‘The enemy is advancing,’ he goes, ‘and they’ll take everything that’s ours. Will you be fighting your battles barefoot? Use your loaf, man amie, and stop your g

loating. We’ve got to think in the long-term. We need to gather supplies for ourselves, and goods to barter with. This isn’t a game of conkers.’

I felt about ten inches tall. ‘But I don’t have anything the Jerries would want.’

Ray pulled his shoulders back and played sergeant-major. ‘Then look sharp and steal it.’

It’s hard to explain now the sway Ray had over me, but there was a lad with such confidence and swagger and I wanted some of it for myself. That wasn’t a crime, was it? I left the thinning crowd and skulked off towards the harbour, brooding on his harangue. Ray was right, there was no two ways about it, I couldn’t sit around and do nothing when these other lads were at it, and if I didn’t own something, perhaps I should steal it. But what? All I’d managed before was an ice-cream off the Vazon cart.

By now I’d drifted across the Esplanade and passed the Albert Memorial, then I didn’t care to walk no more. I rested my elbows on the railings that overlooked our pretty harbour. It was a bright day with a warm breeze and I could feel the sun on my neck. I closed my eyes and remembered all the other summers I’d enjoyed on the island. And that’s when it hit me. I opened my eyes and she was staring me in the face.

Her name was Sarnia Chérie, after the song – ‘Sarnia, chière patrie, bijou d’la maïr’15 – and she was bobbing aside a jetty down the way. A fine little Dory sailboat belonging to my schoolmate, Horace Vaudin. Horace was now away in England, so it wasn’t like he’d be needing her. Of course! I’d loved that little boat as if she was my own. We’d been out on her every weekend that previous summer, up and down the east coast and over to Herm and Sark. There’s a photograph somewhere that shows me perched on her bow, grinning with all my crooked teeth. Reckon I’d just caught the biggest fish because I look so proud, squinting into the sunshine with Herm in the background. I had few talents, I wasn’t quick or clever, but I could handle a boat well enough . . . and there she was, like she’d been waiting for me.

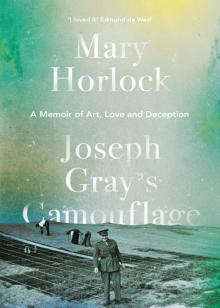

Joseph Gray's Camouflage

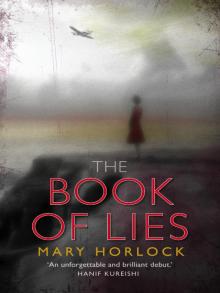

Joseph Gray's Camouflage The Book of Lies

The Book of Lies